15-minute Heritage, city neighborhoods and place identity | Policies for Places

I have already written several pieces here on the idea of the 15-minute city, currently much in vogue in city planning in numerous cities around the world. One of the claims of advocates of the concept is that by ‘living locally’ there can be increased sense of place and place identity and stronger social cohesion among residents. These are usually claimed to be as a result of greater use of public spaces, more active travel and reduced car dependency and more frequent social contact through the use of local shops and facilities.

But there are other factors which can enhance neighborhood identity. One such which is attracting attention relates to the promotion of a shared awareness of local heritage. Inspired by the 15-minute neighborhood approach, there are now some interesting innovative projects aiming to develop what has been dubbed ‘15-minute heritage’.

At the core of the idea is to encourage people to explore the heritage which is on their doorsteps as they go about their daily business. Civic buildings, open spaces and local landmarks ranging from historical ruins to relics of local industry may all lie within a 15-minute walk from home. At the same time as digital technology allows access to museums and heritage sites around the world, increasing awareness of local heritage can foster a richer understanding of place identity and local cultural influences.

Heritage assets

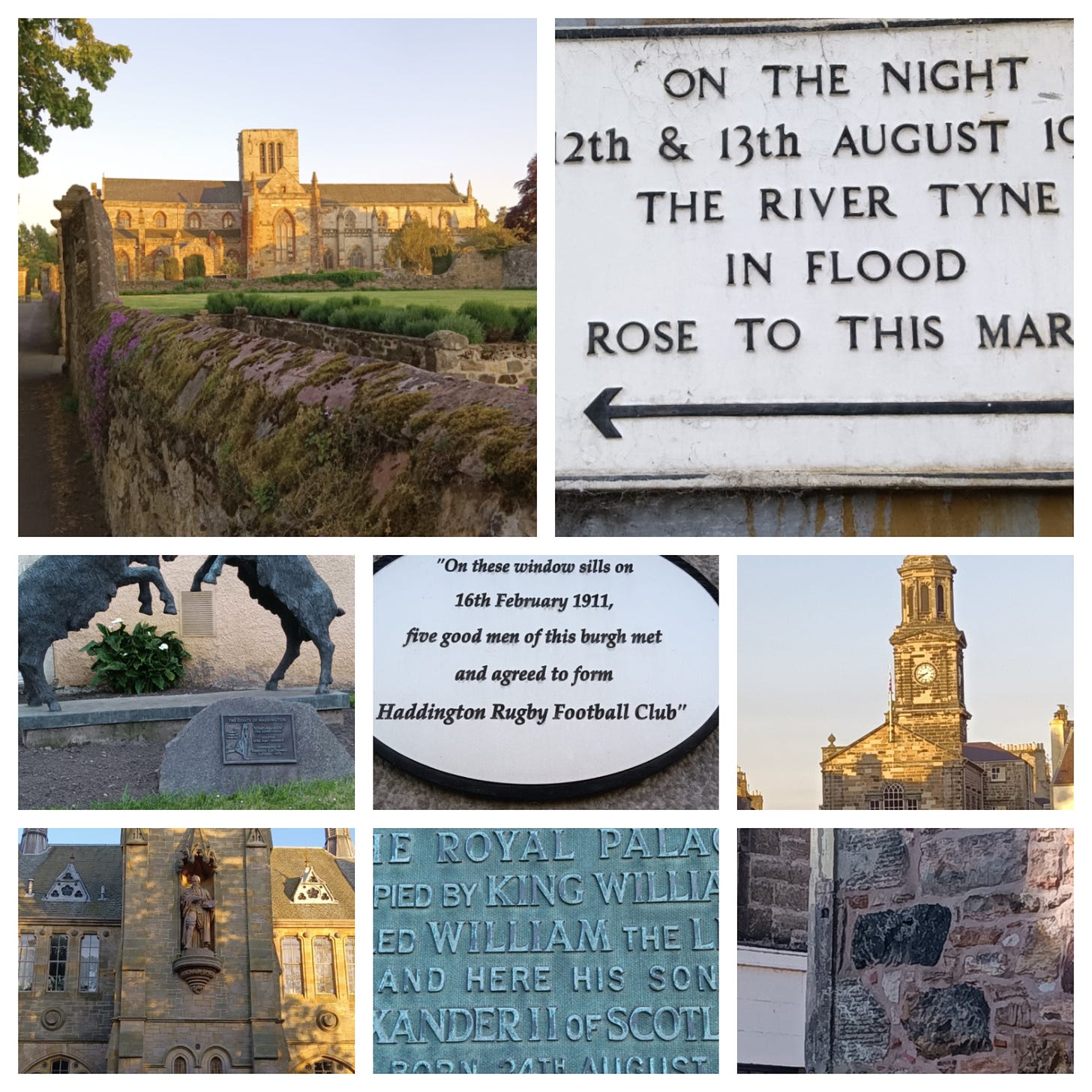

Any observational walk around a neighborhood will reveal all kinds of clues to the heritage of the area. For example, the gallery of pictures here was taken on an evening stroll around the central area of the town where I live. There are street plaques indicating such diverse events as the birth of a Scottish King at a now long-gone Palace in 1198, the founding of the town Rugby club in 1911 and the depth of the great flood in 1932. There are statues of prominent local figures. There are replicas of the town’s historic symbol – the goat. There are intriguing street names, and historic buildings like the recently renovated town hall and the rebuilt parish church, restored 50 years ago after being almost destroyed by Oliver Cromwell in the 17th century.

I could have included many more historical reference points without even visiting the town museum. ‘Heritage’ is much more than castles, historical buildings and museums. It is all kinds of things which can help to produce a sense of place or of place identity, or jog a cultural memory or foster a greater interest in the story of the place in question.

Promoting hyper-local heritage

The 15-minute heritage concept has probably been most fully developed by CADW, an agency of the Welsh Government and part of its historic environment service to encourage communities’ awareness of local heritage. To encourage people to take a greater interest in their local places a grant scheme funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and CADW provides modest grants to local organizations to develop such things as new walking trails, murals, signage and information boards, window displays and the use of digital resources to allow people to explore local heritage assets. The scheme can even include art, theatre and story telling to promote heritage awareness.

Hyper-local heritage – a new role for museums?

The normal expectation for the location of historical information and artifacts is in museums. Museums come in all shapes and sizes from prestigious national institutions to local exhibitions in a few rooms in a local civic building such as a local town hall or a library. For their impact typically museums rely on attracting people in in order to view their exhibits and interpretations of historical events. The 15-minute heritage approach would suggest a wider role in reaching outside the museum building itself to promote the collection of historical assets scattered around a locality.

Nor is this approach something only for essentially local museums. A similar approach can be adopted successfully by larger national museums to enhance knowledge and interest in the city neighborhoods in which they are located, and linking local heritage to larger issues explored in their main collections.

Many museums were hit hard by the COVID pandemic and, as they re-open see it is a time to reflect and re-energize their role. The emphasis now is much more on community engagement, community education and even as engines for social change. Museums may be as much about working with their communities to discover their stories, and finding ways for communities to tell their stories rather than interpreting them themselves. Innovation in the work and approach of museums is encouraged by such awards as the Heritage In Motion award managed by the European Museum Academy. Museums have a key part to play in the delivery of the 15-minute heritage concept.

Impact – the art of the hyper-local

Many of the heritage assets I have mentioned above are often taken for granted by local people who pass them by every day. But there are accounts of how, during COVID lockdown, when many people found themselves confined to living local, many took to exploring their local areas much more closely only to discovered numerus historical references they were previously unaware of. Writers describe how the discovery of these references prompted them to read and research to understand more about the events or people identified and understand more about how local heritage makes and shapes their communities.

As we have seen, big claims are made by the proponents of the 15-minute heritage approach for its impact on notions of local place identity, sense of place and social cohesion is hard to determine. Intuitively these claims would seem justifiable, but place identity and sense of place are hard to define, still less to measure changes over time.

Planning systems across each of the countries in the UK require heritage assessments when local development is likely to change heritage assets or incorporate them in future urban planning, but these rely on heavily on historical data about the asset as the basis for a judgement about its significance. The Royal Society of Arts in the UK maintains a Heritage Index which brings together over 100 indicators into a single score of heritage vitality. The indicators included span both physical and tangible assets as well as social statistics about volunteering, people visiting archives and numbers of nights people spend on holiday in a local area.

The index also attempts to give an indication of the intensity of use of heritage assets with data on the number of young people who are active in heritage through such things as archaeological clubs,, through groups interested in wildlife reserves and through school participation in learning outside the classroom. For more go to www.thersa.org/heritage .

These kinds of measures can provide an indication of some aspects of community engagement with heritage in their local area, but fall short of linking heritage with place identity, sense of place and social cohesion. These links see heritage as a social phenomenon, as a process by which people and communities come to value buildings, practices and traditions as a web of meanings that come together to ‘make place’.

Systematic research to explore these complex processes is itself a complex and challenging undertaking. Writers such as David Seamon and Edward Relph have established a strong theme in human geography about place identity and sense of place which has sought to clarify the subjectivity of place experience, individuals’ attachments to particular places and the role of places in fostering a sense of belonging, but there is work to do to show the role of heritage within that tradition.

There is nevertheless growing practical experience of placemaking through heritage. Heritage can and is mobilized for a variety of present purposes and policy goals. A prominent example is the use of heritage as a catalyst for urban regeneration and economic recovery. The link can be made between heritage as a consumable experience and urban regeneration as economic development, but in so doing the role of heritage in deepening awareness of place and enriching the enjoyment of place should not be overlooked. It is in this respect that the 15-minute heritage concept is vital.

References

D Seamon (2015): Understanding Place Holistically: Cities, Rationality and Space Syntax, Journal of Place Syntax vol 6 no 1

Edward Relph: Overview of Non-place/placelessness ideas at www.placeness.com

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Henrik Zipsane for alerting me to the notion of 15-minute heritage.

Policies for Places | JOHN TIBBITT | Substack. Subscription is free.

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments