The Long-Term Perspective on the Quality of Urban Life

Something about the onset of winter prompts me to take a long-term perspective when thinking about problems.

Living in the northern hemisphere, winter brings the end of the calendar year, which of course leads us to reflect back at least twelve months to assess recent events. Whether we like to admit it or not, we all keep our own annual scorecards.

In addition, being raised Roman Catholic, the onset of winter comes with the annual rituals of observing Christmas, which leads Christians to reflect on events more than two thousand years ago. More years, longer scorecards.

So, sitting at my desk watching the snow fall from the sky on the city where I live (thanks to the Lake Erie snow-making process), it feels natural to take a long-term perspective on the short-term problems that seem to threaten the quality of life that people experience in our cities, not only in the U.S., but across the world.

Each day our favorite newspapers and our trusted social media feeds scream out to us about multiple short-term crises in different domains. These news feeds are accurate. And yet their short-term focus obscures broader long-term trends, many of which project a more positive context within which short-term crises need to be understood.

For example, over the last year the world has experienced no fewer than seven armed conflicts that have each caused more than ten thousand deaths and hundreds of thousands of injuries. Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine and the more recent attack by Hamas on Israel bring fresh stories every day of historically significant bloodshed and destruction. Other conflicts get less attention in Western newsfeeds. Yet each brings misery and ruin to millions of residents of cities and regions. They include armed conflicts in Sudan, Myanmar, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and the ongoing drug wars in nearby Mexico.

Coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic is another domain. The global pandemic has subsided, but its effects remain serious. The World Health Organization reports more than 772 million confirmed cases of COVID in cities and regions across the globe since its initial outbreak in early 2020, with 6.9 million confirmed deaths. Both numbers are clearly underestimates because of uneven and unreliable reporting. No part of the urban world has been spared from the negative consequences of this global pandemic. And public health officials remind us that the next global pandemic may be even worse.

The news about climate change is a third domain filled with short-term crises. The year 2023 is on path to become the warmest year since reliable climate records have been kept. The evidence of human-induced global warming continues to pile up. The 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) starts up in two days in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The U.S. government just released its fifth National Climate Assessment report, which provides stark details of how climate change is already creating billions of dollars of damage in the U.S each year.

Many commentators like to characterize Americans as having anti-urban biases. Yet in the last fifty years, Americans have invested trillions of dollars building and rebuilding magnificent cities and their surrounding urban regions. Most are located along inland waterways and coastal regions. The National Climate Assessment, however, clearly describes how many of those cherished places are threatened by rising sea levels, extreme summer heat, and destructive super storms.

Daily stories about crises in each of these domains fuels a fourth, which is the ongoing story that proports to prove that democratic governance institutions around the world are unable to cope with these cascading domains of short-term crises.

Anti-democratic political organizations, both state-sponsored and independent, use sophisticated propaganda strategies to leverage social media feeds to propagate lies and half-truths to convince people that democratically authorized governance processes, especially those that govern our most diverse cities and urban regions, are overwhelmed by the scale and scope of current crises. They do this by disrupting long-cherished patterns of democratic self-governance, especially voting, and by undermining the social trust and mutual respect for diverse opinions and diverse interests on which democratic processes rely.

Urbanized democratic institutions, they argue, are especially corrupted by too many special interests that cater to powerful elites and socially bazaar niche groups that band together to victimize ordinary people. The result, they project, is social chaos, leftist threats to traditional social values, random violence, and the breakdown of property rights, personal freedoms, and public safety.

The solution, according to anti-democratic propaganda, is a new age of authoritarian governance. Existing authoritarian regimes (especially China, Russia, and Iran) are praised for their capacity to overcome social chaos, especially in their urban centers, and replace it with orderly, rational public policies that will restore the rule of law (usually by willfully violating existing laws), enforce traditional social values, and pursue what's best for most citizens.

In today's crisis-driven world, authoritarians argue that the scale and scope of the global problems we face has turned democratic governance into a quaint, antiquated luxury that is unable to chart a wise path forward for complex, technologically sophisticated 21st Century human societies.

Despite the very real challenges of short-term crises, however, we need to put today's problems into a longer-term context. A longer-term perspective is the most powerful way to undercut the fearmongering and socially divisive wedges that authoritarian propaganda seeks to propagate in its aggressive attempt to destroy the legitimate social authority of democratic institutions.

One powerful tool that can help achieve this goal is the Human Development Index (HDI) that has been created by the United Nations. Before the HDI, the most used measure of progress in countries around the world since the end of World War Two has been Gross Domestic Product, or GDP. GDP measures the total financial value of all goods and services each nation produces within a specific year. Yet this measure has been widely criticized since it measures only financial value. Furthermore, it does not even try to address the inequitable distribution of that one flawed measure.

Consequently, the UN created the HDI, which captures three broad dimensions of the quality of life experienced by most common people in each of the world's nations. The three dimensions are health, education, and the standard of living. In the words of the UN,

"The health dimension is assessed by life expectancy at birth, the education dimension is measured by mean of years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and more and expected years of schooling for children of school entering age. The standard of living dimension is measured by gross national income per capita. The HDI uses the logarithm of income, to reflect the diminishing importance of income with increasing GNI. The scores for the three HDI dimension indices are then aggregated into a composite index using geometric mean."[i]

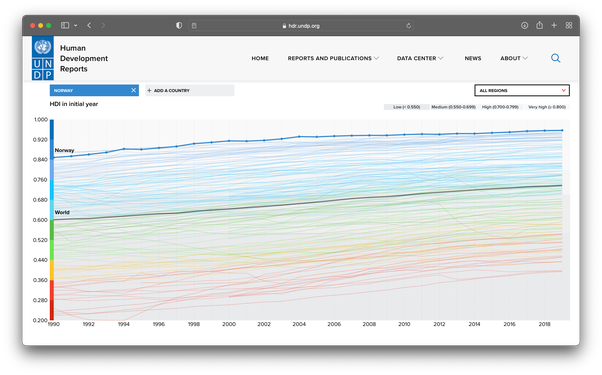

The figure below illustrates the upward movement of the HDI in each of the world's nations from 1990 to 2021. The figure has too many lines to examine in detail. Yet the dark line in the middle tells the overall story.

Between 1990 and 2021, billions of people across the world experienced tangible improvements in their quality of life as the World’s composite HDI rose from .601 in 1990 to .732 in 2021, a 21.8 percent increase in the span of three decades. Life expectancy has increased substantially. Educational attainment has skyrocketed. And dramatic improvements in individual income have transformed the material basis for the quality of life for residents in almost every nation.

These numbers may seem abstract, but they represent aggregate measures of billions of lived experiences among people in almost every part of the world, in almost every contemporary culture, not just a few highly developed nations. Horrible inequalities still exist, of course. And there is still much progress to achieve. But placing these data in an even longer-term perspective helps to underscore the remarkable progress that has been achieved during our own lifetimes.

Modern humans have been around for almost 300,000 years. Small groups of humans began to adopt our current lifestyle of living in permanent settlements only about 10,000 years ago. Most people who were alive at any time continued experiencing different forms of hunter-gatherer lifestyles until less than 1,500 years ago. Material abundance was enjoyed by only a handful of people in settled human cultures until only about 700 years ago. And, by the end of World War Two, the vast majority of settled people continued to live with material deprivation as a permanent component of daily life.

In just the last thirty years, more than 2 billion people rose from the permanent experience of material poverty to a level of basic, short-term, material security. In those same years, another 2 billion people rose from basic, short-term material security to a standard of living that is recognized as middle class. The speed of this rise, and the widespread distribution of these changes on every continent is astounding when looked at through the longer-term lens of the history of settled human cultures.

Two contributing factors to this historic progress in the lived quality of contemporary human lives need to be recognized. The first is that widespread urbanization has been a fundamental component of this transformation. The growth of cities and their sprawling urban regions are central players in this record of progress.

The second is that widespread advances in economic and social self-determination have been essential to each nation’s capacity to improve its citizens’ quality of life. Improvements have occurred most rapidly where traditional social authorities of government, religion, violence, and wealth have loosened their control over non-elite and/or non-privileged people. Nations with less rapid improvements are those where traditional sources of social authority refuse to yield control.

The unprecedented upward surge in the quality of life that billions of people alive today are experiencing is, no doubt, causing unprecedented challenges to our processes of urbanization and the processes of self-governance in every contemporary human culture. In addition, we can no longer ignore the fact that the upward surge has been fueled largely by burning fossil fuels. One fact that helps underscore this point is that more than half of the airborne carbon that is currently warming our global climate has been put into the atmosphere by humans since the year 2000.

Yet we can’t forget the long-term context. Today’s global upheavals, and the multiple domains of short-term crises we experience each day in our news feeds, are driven by fabulous rises in the quality of life among contemporary humans.

Solving those crises will not occur if we abandon the importance that both cities and increasingly democratic governance institutions have played, and are playing, in these transformative improvements. Adopting anti-urban policies, and embracing anti-democratic, authoritarian leaders who seek to dismantle our most cherished democratic governance institutions threatens to reverse the most productive era of human progress that our species has ever experienced.

Bob Gleeson

[i] For more detailed information, see www.hdr.undp.org.

Source: Substack

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments