"More Perfect" Solutions to Urban Problems - The Urban Lens Newsletter

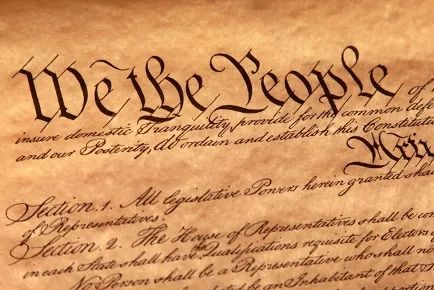

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

The most important three words in this, the Preamble to the US Constitution are surely, “We the people.” This well-known key phrase, “we the people” means that the Constitution aims to incorporate the visions of all Americans and that the rights and freedoms bestowed by the document belong to all citizens of the United States of America. But while perhaps slightly less important, what I want to consider today is its successor phrase, “‘In order to form a more perfect union.”

The Preamble is sometimes called the Enacting Clause, because it spells out why the Founders thought we should have and need a Constitution. It gives us the best overview of what they had in mind as they hashed out the basic rules and arrangements of the three branches of government. Specifically, it tells us that the framer’s intention was not to form a perfect union, but instead a more perfect one. What they had in mind specifically was to recognize that the old government based on the Articles of Confederation was extremely inflexible and limited in scope, and that this made it hard, at best, for the government to respond to the changing needs of people over time. They were seeking to improve the state of the nation, not necessarily to perfect it.

This distinction here between “perfect” and “more perfect” may be subtle but it is of real practical consequence. During the twentieth century, both Marxism-Leninism and National Socialism were put forth as if they were based upon definitive social postulates that would lead to the perfect society. Yet both ravaged societies and cost tens of millions of lives.

The distinction is in many ways no less important when considering solutions to the myriads of problems found today throughout America’s complex urban systems.

If one assumes and holds in mind the idea of complete perfection as the appropriate ideal or standard against which to judge public policies and outcomes, then one will always find oneself dissatisfied and despairing of the disparity between this ideal and the actual conditions we commonly experience. On the other hand if one assumes and accepts that our social systems are imperfect, as the founders did, and holds up the ideal or standard of striving to improve them, one stands a much better chance of contributing to solutions rather than to problems.

The distinction is of real practical consequence because it helps demarcate two conflicting visions of morality and human nature currently playing out in American society. In a marvelous April 27, 2023 opinion piece in the New York Times, David Brooks referred to one of these visions as “amoral realism.” The idea is that perfection is impossible, so why even bother to try to bring conditions in the world closer to it. As Brooks put it, this vision says, “we live in a dog-eat-dog world. The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. Might makes right. I’m justified in grabbing all that I can because if I don’t, the other guy will. People are selfish; deal with it.” The pitfall of this vision is a morally ambiguous authoritarianism in which cruelty, dishonesty, vainglory and arrogance among public officials and other leaders can be valorized as strength and survival skill.

The Founders, on the other hand, made clear in the Preamble that they held the conflicting vision in which the widespread exercise of democratic morality is the better ideal to strive for. As they saw it, the “people” (not dollars) are the plenary units of ultimate value in society, each individual citizen has some inherent value worthy of social recognition, and all citizens should have equal input into the selection of those who can influence the policies that shape the lives of citizens. In their vision, the future vitality of the American nation depended upon the design and conduct of institutions dedicated to sustaining a full, vigorous measure of autonomous intellectual life, including an appreciation of rational thought, knowledge, and wisdom, freedom of speech, legal equality, due process, religious liberty, and sanctity of conscience. While they assumed and accepted that the world is imperfect, they did their best to set up a set of institutional arrangements which would improve the nation, and enable it to adapt and change so as to bring it closer to the ideal they held in their vision of morality and human nature.

When in writing the Preamble the Founders compared the imperfect world in which they found themselves living to the better world they hoped to create, they got it exactly right. They were not bewailing and bemoaning the imperfections in society, casting aspersions and blame, and claiming that only they could solve the problems through the exercise of their own immaculate perception and authority. Rather they simply recognized the problems that existed in the society at the time and accepted the responsibility to take some initiative to solve or ameliorate them. By seeking to improve rather than to perfect society, they avoided the pitfalls of amoral realism and in doing so they contributed to solutions rather than to problems of the then-new nation.

The Founder’s sought to realize essentially moral and decent ideals of a better society by taking steps to improve it, not necessarily to make it perfect. This is where we should aim in our urban systems today. The Preamble reveals that they recognized and accepted that regardless of their own values and preferences some things about the society and world they occupied at the time could not be changed. Also, the very existence of the document makes clear that they had the moral courage to attempt to change some of the things that they believed could be changed. And they seem in many instances, but not all, to have had the wisdom and foresight so to recognize the difference between the things they could change and the things they could not. In this way they set an excellent example for today’s urban policy makers as well as for those of us interested in the solutions to today’s urban problems.

Bill Bowen

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments