Putting traffic in its place: time for a new culture of transportation | Policies for Places

So the UK Prime Minister has declared he is ‘on the side of the motorist’ in the aftermath of a parliamentary byelection in which the imposition of an extended ultra-low emission zone (ULEZ) was a major issue. Other attempts at controlling traffic movement in towns and cities in the UK through measures such as low traffic zones (LTZs) or controlled parking zones (CPZs) are also meeting opposition, and are being postponed (as in Oxford, Bristol and elsewhere) or abandoned. All this, when the social, environmental and health benefits of lower traffic seem clear, and popular support for environmental action remains firm.

Whilst there has probably always been an uneasy relationship between traffic and other users of roads and streets, managing that relationship effectively to secure the mutual benefits for all involved has become more complicated in the face of rising numbers of vehicles and vehicle journeys and against the urgency of issues of global warming, zero carbon, cleaner air and risks to public health, and the economic sustainability of towns and cities in the face of changing technologies and work patterns. It is time to re-assesses strategies employed to respond to the issues raised.

Some context

The last 50 years have seen us become a heavily car-dependent society. The number of cars on British roads has increased from around 19m in 1971 to around 37m in 2022. Predictions that we had reached ‘peak car’ made a decade ago seem premature as the rising trend continues. Despite the growing pressures on urban space many cities continue to try to accommodate car growth through improvements to road capacity and traffic flow, and more parking space. On the other hand, some other cities, have realized the need to reduce car journeys and have introduced a range of measures to make car ownership more expensive through increased parking charges, or less convenient by restricting car access to areas of the city through street closures and zoning as described above. Some have moved more proactively to reduce car dependence through investment in public transport services or opportunities for active transport.

It is apparent that restrictions on cars is very often met with fierce resistance even in the face of sound evidence of the benefits to the livability of cities, as people argue that it is ‘unfair’ to bear down on the car in this way. Whilst there is a continuing debate about how to assess what would be a fair allocation of road space, it is clear that there is a major challenge for cities about how to achieve transformative urban transportation whilst also minimizing social disruption.

Basis for progress

Progressive moves will need planners to pay more attention to the social and psychological significance of both the car on the one hand and of the street on the other.

Cars constitute highly personalized spaces with significance far beyond the function of providing a means of transport from one place to another. Cars are symbols of social status. Cars provide a means to socializing with family and friends and reaching other communities and interests. Cars have associations with feelings of protection and personal safety. Urban design has often created car dependency in accessing community facilities and facilitating the delivery of mobile personal services. Small wonder then that interventions against the car can represent a personal threat to some as well as disruption to established ways of living.

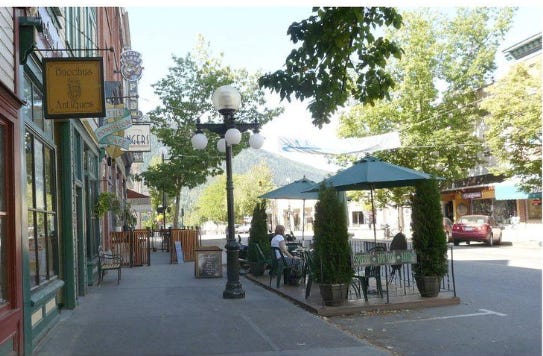

Similarly streets are not just spaces which facilitate mobility, but are one of the most valuable public spaces each community has. Neighborhood streets are places to share, not just to drive through with as few delays as possible. Organizations such as PPS Placemaking and Strong Towns promote the value of streets which offer varied activities and destinations, when they are safe, when they allow social interaction and when they are readily accessible. Too much traffic is a threat to many of these features of successful streets.

Strategic approach to culture change

So how do cities find a way to acknowledge these pressures in a progressive approach to transformative change? In broad terms urban transport systems need to address three main elements. First, cities need viable alternative transport offers for suburban and rural commuters and city visitors. Second they need a comprehensive infrastructure that encourages active mobility within the city. Third, they need communication strategies which frame the need for culture change in ways which address popular concerns, and especially those of drivers. All three elements need to be taken forward in tandem. Of these the third, the need for a focused communication strategy is arguably the most neglected by urban planners and also the most essential.

It is apparent that attempts to rationally explain car restrictions will rarely work. Rather, both rational and emotional arguments need to be made which aim to make non-car use more attractive and to justify interventions that may be otherwise perceived as ‘anti-car’.

It will not be helpful for the communication strategy to argue against the car directly or indirectly or dwell on the harm caused by motorized transport or the challenges of climate change and net zero. Communications should focus on benefits from active travel, such as greater average speeds and better health, and portray bicycle use and active travel as an aspirational identity.

Traffic users will always weigh their options. Against the backcloth of a communication strategy positively appealing to the social and psychological significance of alternative modes of travel and the more general goal of transport culture change, steps can also be taken to make driving less comfortable. Cities can be more energetic in enforcing regulations about parking restrictions or speed limits and fining offenders.

By devoting more street space to alternatives to car transportation cities can demonstrate the benefits of change which will help change public perceptions of ‘micro-mobility streets’ such as improved public safety and livability and the attractiveness of walking or cycling for a greater awareness of what their place has to offer. Car drivers might also come to welcome such a separation of traffic as increased take-up of active travel opportunities lowers demand for road space and lowers the risk of accidents.

Imaginative support schemes can provide further incentives to change travel habits. For example a small grants scheme to encourage people to repair and restore cycles has produced a measurable increase in cycle use and reduced car journeys whilst imaginative car scrappage schemes can help motorists to adapt to changing traffic requirements.

A new culture of transportation

Urban planners and politicians throughout the world are confronted with the challenge of reconciling transport needs with the demand for more livable cities against the background of the risks from climate change. There is always a tension when existing urban design has to try to accommodate new modes of transport. The narrow streets in the centres of many European cities were never intended as thoroughfares for cars and lorries. The expanding cities of the early 20th century tended to separate business, industrial and cultural zones from peripheral suburban and residential space, producing a car-based culture for daily living and demanding ever more road space for ever more cars. Now, new communication technologies and changes in work practices are leading to new styles of urban living which embrace developing digital communication. Arguably these recent changes, spurred by experiences during the covid pandemic, could lead to a reduced requirement for physical travel and greater appreciation of the benefits of local living in a flourishing local neighborhood.

Surely an opportunity for a new culture of transportation to match changes to urban living is presenting itself. Whilst there is a debate to be had about the values on which such a new culture might be based, amongst them must be:

- Social inclusion – a culture that recognises that different social groups will have different legitimate transportation requirements

- Equity in accessing appropriate modes of transportation – urban design needs to accommodate access for all and facilitate use of alternative modes

- Recognises the benefits to all from cleaner air

- Recognizes the importance of supporting communities and vibrant neighborhoods which are safe for users and encourage social interaction

- Recognizes the importance of heritage and public spaces for fostering place identity and social cohesion.

So to go back to where I began, a new culture of transportation will recognize motor traffic as a legitimate component of place, but not the dominant component, and one that risks seriously limiting the cohesive communities so many desire.

Further reading

Stefan Gosling (2020) Why cities need to take road space from cars – and how this could be done, Journal of Urban Design 25/4

https://www.livingstreets.org.uk

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments