What's a City to Do? (About Global Warming) | The Urban Lens Newsletter

Until recently, international and national agencies have played the most visible roles in dealing with global warming. International and national agencies funded decades of scientific research that transformed our understanding of Earth’s climate systems. The United Nations-sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is now the most authoritative source of scientific consensus about global warming. The IPCC’s most recent Synthesis Report (AR6), released just last month, begins with the following statement:

Human activities, principally through emissions of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally caused global warming, with global surface temperature reaching 1.1°C above 1850–1900 in 2011–2020. Global greenhouse gas emissions have continued to increase, with unequal historical and ongoing contributions arising from unsustainable energy use, land use and land-use change, lifestyles and patterns of consumption and production across regions, between and within countries, and among individuals.[i]

Almost every national government in the world now has some form of Climate Action Plan that includes specific goals for reducing the emission of greenhouse gases. Each nation’s goals are known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Many developed nations have begun to allocate substantial resources to achieve their own NDCs. The U.S. has recently allocated hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade. In addition, most international agencies are trying to pilot innovative financing models to help lower-income nations do the same.

But, as the latest IPCC summary makes clear, the world’s emissions of greenhouse gases continue to increase, not decrease. Actions are not yet on track to meet the goals that have been set. And the NDC goals are themselves too modest to assure the overall goal of preventing global temperatures from rising more than 1.5 to 2.0 degrees Celsius before 2100.

Two types of actions are needed at much greater scale: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation actions directly address the causes of global warming, i.e., the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere by human activities. Adaptation incudes actions to reduce the harms that are already beginning to occur because the atmosphere is warming. The IPCC’s most recent, carefully worded statements reveal deep frustration about the lethargic pace of action.

Rapid and far-reaching transitions across all sectors and systems are necessary to achieve deep and sustained emissions reductions and secure a livable and sustainable future for all. These system transitions involve a significant upscaling of a wide portfolio of mitigation and adaptation options. Feasible, effective, and low-cost options for mitigation and adaptation are already available, with differences across systems and regions[ii].

In other words, the scientists and policy researchers in the IPCC report that solutions do exist for most of the problems of global warming. They are feasible, effective, and even affordable. They vary across different systems and in different places. But none will make any difference unless the world moves into a new era of aggressive implementation. The decade of the 2020s is perhaps the last chance to begin setting the world on a trajectory to achieve meaningful mitigation and adaptation.

All global modelled pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C … to 2°C … involve rapid and deep and, in most cases, immediate greenhouse gas emissions reductions in all sectors this decade. Global net zero CO2 emissions are reached for these pathway categories, in the early 2050s and around the early 2070s, respectively.[iii]

National governments can set overall goals. And national governments have the unique ability to allocate large amounts of capital. But aggressive implementation of current NDC’s for every nation in this decade will require widespread, innovative, and thoughtful, action at the local level too. Cities are essential players.

But what can local actors really do? Let’s focus first on mitigation.

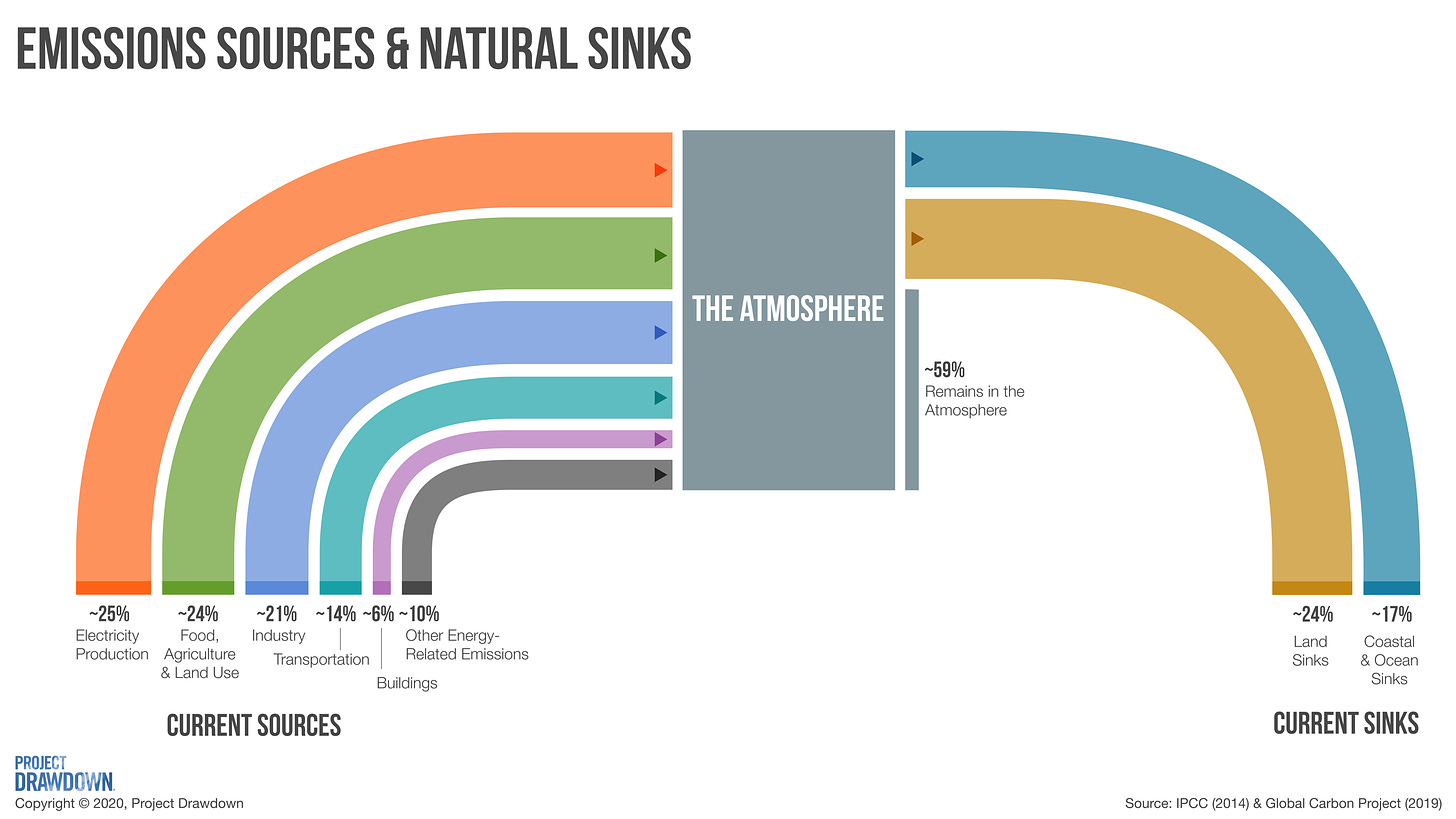

The graphic below was created by a non-profit organization named Project Drawdown using data from the IPCC.[iv] It visualizes how humans add greenhouse gases into the atmosphere through different activities.[v] Small increases in these greenhouse gases in the atmosphere cause more of the sun's heat to be retained, thus slowly warming the atmosphere's average temperature. The warmer atmosphere also transfers heat to the land and the oceans.

The graphic uses global data from 2019 to show that twenty-five percent of the greenhouse gases we emit across the world come from the ways we produce electricity. Twenty-four percent comes from agricultural practices and other ways we use land. Twenty-one percent comes from our manufacturing industries, fourteen percent from our transportation systems, six percent from the ways we construct, maintain, and use our buildings, and the remaining ten percent is emitted by other parts of our energy systems.

The atmosphere is not a static thing, it’s a complex system constantly in motion. Consequently, the graphic also shows that many natural processes remove these greenhouse gases from the atmosphere each year. These are known as sinks. Plants that grow on land or in the oceans, for example, extract large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

The graphic shows that on net, about 41% of the amount of greenhouse gases that human activities across the planet put into the atmosphere in 2019 were cycled back out of the atmosphere into land or oceans sinks that year. But 59% remained in the atmosphere.

Humans have been adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere for at least 150 years. Every nation, sub-national region, province, state, and local municipality has evolved its own unique portfolio of greenhouse-gas-emitting power plants, industries, buildings, transportation networks, and nearby agricultural areas. Every place on Earth also has its own portfolio of carbon sinks.

The net amounts of greenhouse gases that remain in the atmosphere each year have skyrocketed in recent decades because human systems of population growth, mass production, energy consumption, transportation, and better nutrition have grown explosively. One estimate is that almost half the greenhouse gases that humans have put into the atmosphere since 1850 have been put there since the year 2000.

Project Drawdown has carefully analyzed more than 100 specific initiatives that can reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and/or improve the capacity of sinks to help remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The result is a rich menu of potential solutions in each category of human activities that emit greenhouse gases and in each type of carbon sink. A customized strategy for action can be matched to specific information about each nation, sub-national region, province, state, and local area, depending on the specific details of different parts of the world.

In the U.S., President Biden revised the national NDC goal shortly after he took office in January of 2021. The revised goal is to reduce U.S. carbon emissions to 50% of 2005 levels by the year 2030. But national goals don’t implement themselves, especially in a federal system that includes fifty states, the District of Columbia, and several territories. Most states contain many different local areas with different portfolios of carbon emitting activities and natural carbon sinks. As of the end of 2022 only 33 states have established their own Climate Action Plans. Some are sophisticated, some are rudimentary. Most have not adjusted their plans to the new NDC goals. And many of the remaining states refuse to even begin the process of developing a statewide Climate Action Plan, often because their elected statewide leaders do not accept the IPCC’s scientific consensus that climate change is a problem to be addressed.

The story changes at the local level though. One listing maintained by the Zero Energy Project, which is a non-profit group that represents the builders of zero net energy homes, provides active links to the Climate Action Plans for more than 700 American cities, with examples in every state.

Most of this activity in local governments throughout the U.S. predates the Biden Administration’s new NDC goals. And all of it predates the large infusion of Federal dollars from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2022 (also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act) and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

A broad national movement, led by cities, is creating a new era of greenhouse gas mitigation efforts in almost every state throughout the U.S. This new movement is certainly in its early formative period, and not much is known yet about its impact. But hundreds of billions of dollars of Federal funding are now beginning to be allocated. And more than 700 American cities have some type of plan, however rudimentary. This local movement certainly has a major role to play if the U.S. intends to meet its NDC commitments within the time frame that the IPCC urges all national to adopt. City-level Climate Action Plans have great potential for creating a new wave of thoughtful, customized initiatives that can lead to aggressive actions to begin mitigating greenhouse gas emissions in this decade.

Bob Gleeson

[i] IPCC AR6, Headline Statements A.1, released March 20, 2023.

[ii] IPCC AR6, Headline Statements, C.3, released March 20, 2023.

[iii] IPCC AR6, Headline Statements, B.6, released March 20, 2023.

[iv] See www.drawdown.org.

[v] The three so-called "greenhouse gases" are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O).

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments